News

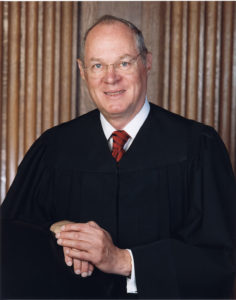

Justice Kennedy’s Jurisprudence of Dignity

As we near the anniversary of the landmark Supreme Court ruling in Obergefell on June 26, 2015, it is well to remember that marriage equality is greatly indebted to Justice Anthony Kennedy and his jurisprudence of human dignity.

Even as we mourn the tragedy of Orlando, and as we feel beleaguered by the forces of hatred and intolerance, we need also to count our blessings, among which is the vision of equality promulgated by Justice Anthony Kennedy in his rulings on behalf of equal rights under the law for all.

Justice Kennedy is author of four historic gay rights rulings from the Supreme Court, Romer v. Evans (1996), Lawrence v. Texas (2003), U.S. v. Windsor (2013), and Obergefell v. Hodges (2015). These decisions, each building upon the other, are marked by a deep concern for human dignity. More precisely, they address forthrightly the ways in which discrimination against lgbt individuals is an affront to personal dignity. Indeed, his rulings on gay rights may be said to constitute a jurisprudence of human dignity, one that has expanded and given heft to the principle of equal protection under the law.

In November 1987, after the failed nominations of Robert Bork and Douglas Ginsburg, Justice Kennedy was nominated by President Ronald Reagan to the Supreme Court seat vacated by Lewis F. Powell, Jr. Kennedy, who had been appointed to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit by President Gerald Ford in 1975, was elevated to the Supreme Court by a 97-0 vote in the U.S. Senate on February 3, 1988.

President Ronald Reagan with Supreme Court nominee Anthony Kennedy, Nov. 11, 1987

President Ronald Reagan with Supreme Court nominee Anthony Kennedy, Nov. 11, 1987

Kennedy’s appointment came in the wake of the disastrous Supreme Court ruling in Bowers v. Hardwick (1986), a 5-4 decision that upheld the criminalization of private, consensual sexual activity. In the majority opinion, Justice Byron White dismissed the claim that homosexuals had a right to sexual privacy as “at best, facetious.” A concurring opinion by Chief Justice Warren Burger blatantly invoked Biblical condemnations of homosexuality.

Justice Lewis Powell initially voted to find sodomy laws unconstitutional, but in the course of deliberations he reluctantly cast the fifth vote to uphold them. Later, after the decision in Bowers v. Hardwick had been roundly denounced as one of the worst decisions ever issued by the Supreme Court, Powell ruefully acknowledged that he probably erred in voting as he did.

Justice Kennedy thus joined a Supreme Court that was deeply divided on the question of gay rights, but had recently ruled that the Constitution allowed states to criminalize homosexual conduct. It seemed unlikely that the Court would reverse direction any time soon.

A Bare Desire to Harm

In 1996, however, Justice Kennedy authored a decision on behalf of a 6-3 majority that marked a momentous change in the Court’s posture toward gay rights. In Romer v. Evans, the Court invalidated Colorado’s Amendment 2, a constitutional amendment enacted by popular vote in 1992 that prohibited municipalities and state agencies from granting lesbians and gay men “protected status,” and denied them the right to bring any “claim of discrimination.”

In his remarkable opinion, Justice Kennedy explained clearly that the purpose of Amendment 2 was not, as the state alleged, merely to deprive homosexuals of “special rights,” but rather to harm gay people in a host of ways. That is, it was motivated by “a bare desire to harm a politically unpopular group.”

Asserting that “Central both to the idea of the rule of law and to our own Constitution’s guarantee of equal protection is the principle that government and each of its parts remain open on impartial terms to all who seek its assistance,” Justice Kennedy articulated a concept of equal protection that is both inclusive and also suspicious of the motivations of legislators and voters, especially when they may plausibly be motivated by animus.

He described Amendment 2 as “a status-based enactment divorced from any factual context from which we could discern a relationship to legitimate state interests; it is a classification of persons undertaken for its own sake, something the Equal Protection Clause does not permit.”

Amendment 2, he concluded on behalf of the Court, “classifies homosexuals not to further a proper legislative end but to make them unequal to everyone else. This Colorado cannot do. A State cannot so deem a class of persons a stranger to its laws.”

As Gregory Johnson has observed, “Romer marks the first time in its history that the Court recognized lesbians and gay men as worthy and deserving of equal rights. The decision helped stem the tide of anti-gay initiatives that were spreading across the West in the late 1980s and early 1990s. The case is also important because it laid the groundwork for other important gay rights decisions.”

Dignity as Free Persons

Preeminent among the other gay rights decisions is Lawrence v. Texas (2003), in which Justice Kennedy authored a decision that reversed Bowers v. Hardwick and struck down laws criminalizing private homosexual conduct in the strongest possible terms. As a result of the court’s broad declaration in Lawrence v. Texas, laws in the 13 remaining states that made sodomy a crime were invalidated and the Court asserted respect for the private lives of homosexuals.

In the decision handed down on June 26, 2003, Justice Kennedy, joined by Justices Stephen Breyer, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, David Souter, and John Paul Stevens, ringingly endorsed due process and the right to privacy. Gay men and lesbians, the majority held, are “entitled to respect for their private lives . . . The state cannot demean their existence or control their destiny by making their private sexual conduct a crime.”

At the heart of the decision is Justice Kennedy’s characteristic concern for liberty and human dignity: “The liberty protected by the Constitution allows homosexual persons the right to choose to enter upon relationships in the confines of their homes and their own private lives and still retain their dignity as free persons.”

Moreover, the Court recognized the stigmatizing effect of sodomy laws even when they are rarely enforced or are deemed minor offenses. Justice Kennedy observed that while the Texas statute under review was but a class C misdemeanor, it nevertheless remained “a criminal offense with all that imports for the dignity of the persons charged.”

He added: “When homosexual conduct is made criminal by the law of the State, that declaration in and of itself is an invitation to subject homosexual persons to discrimination both in the public and in the private spheres.”

Of Bowers v. Hardwick, Justice Kennedy wrote, “Its continuance as a precedent demeans the lives of homosexual persons.” He declared emphatically: “Bowers was not correct when it was decided, and it is not correct today. Bowers v. Hardwick should be and now is overruled.”

The Court’s ruling in Lawrence v. Texas is the most significant legal victory in the history of the gay rights movement. It changed the legal landscape in which gay men and lesbians live in the United States. By acknowledging the legitimacy of gay and lesbian relationships, the Supreme Court gave the glbtq movement a new credibility in debates about issues as diverse as adoption, parental rights, employment and licensing rights, service in the military, partner benefits, and marriage.

As Dale Carpenter observed in his authoritative book on the case, Flagrant Conduct, The Story of Lawrence v. Texas (2012), “Before Lawrence, when it was possible for a state to criminalize the sexual lives of gay people, it was much easier to deny them a host of the other rights and privileges taken for granted by most Americans. Before Lawrence, it was logical to say the government could disfavor them in jobs where they might be regarded as role models, like police officers and teachers. It was possible to believe that they, like any class of criminals, should be watched around children, even their own, or should be altogether prohibited from adopting and raising kids. . . . And if their sexual conduct could be made a crime, it was no stretch to declare that their relationships need not be formally recognized by the law, including in marriage.”

[Carpenter discusses his book and Lawrence v. Texas in this video.]

While the Lawrence opinion pointedly reserved the question of marriage recognition for another day, that question is at the forefront of Windsor and Obergefell, the two subsequent gay rights decisions authored by Justice Kennedy.

The Principal Purpose Is to Impose Inequality

Windsor v. U.S. was filed by the ACLU LGBT Project in November 2010 on behalf of Edie Windsor. It sought to declare Section 3 of the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA) unconstitutional.

Enacted at a time when conservatives feared that Hawaii or Alaska or other states might adopt same-sex marriage, DOMA, which was signed into law by President Bill Clinton on September 21, 1996, after having been passed by a vote of 342-67 in the House of Representatives and a vote of 84-14 in the Senate, relieved states and other jurisdictions of the obligation to recognize same-sex marriages and marriage-like relationships authorized by other jurisdictions: “No State, territory, or possession of the United States, or Indian tribe, shall be required to give effect to any public act, record, or judicial proceeding of any other State, territory, possession, or tribe respecting a relationship between persons of the same sex that is treated as a marriage under the laws of such other State, territory, possession, or tribe, or a right or claim arising from such relationship.”

Section 3 defined marriage as a union of one man and one woman for the purposes of federal law: “In determining the meaning of any Act of Congress, or of any ruling, regulation, or interpretation of the various administrative bureaus and agencies of the United States, the word ‘marriage’ means only a legal union between one man and one woman as husband and wife, and the word ‘spouse’ refers only to a person of the opposite sex who is a husband or wife.”

Windsor and her late spouse Thea Spyer lived together for 44 years. They were married in Canada in 2007. Although their marriage was recognized by New York, because of Section 3 of DOMA, the federal government was prohibited from recognizing it. Windsor was thus forced to pay more than $350,000 in federal estate taxes when Spyer died in 2009. Had their marriage been recognized, Spyer’s estate would have passed to Windsor without any tax.

In December 2012, the Windsor case, after favorable judgments in District court and at the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, was granted review by the United States Supreme Court, where it was now called United States v. Windsor.

In a 5-4 decision released on June 26, 2013, the Court struck down Section 3 of DOMA, ruling that it violated equal protection principles.

Justice Kennedy’s decision finessed the question of whether laws involving sexual orientation should be reviewed under a deferential rational basis examination or should be subject to strict scrutiny. Instead, he declared that suspicious laws should be subject to “careful” review, thus inching close toward placing sexual orientation classifications in a “suspect” or “quasi-suspect class,” along with race, religion, national origin, gender, and legitimacy of birth.

Crucial to Justice Kennedy’s decision is the determination that DOMA was enacted out of animus. Like Colorado’s Amendment 2, DOMA was passed into law simply to injure same-sex couples. “DOMA’s unusual deviation from the usual tradition of recognizing and accepting state definitions of marriage here operates to deprive same-sex couples of the benefits and responsibilities that come with the federal recognition of their marriages. This is strong evidence of a law having the purpose and effect of disapproval of that class. The avowed purpose and practical effect of the law here in question are to impose a disadvantage, a separate status, and so a stigma upon all who enter into same-sex marriages made lawful by the unquestioned authority of the States.”

The decision described DOMA’s principal effect as “to identify a subset of state-sanctioned marriages and make them unequal. The principal purpose is to impose inequality. . . .”

The law, Kennedy continued, “undermines both the public and private significance of state-sanctioned same-sex marriages; for it tells those couples, and all the world, that their otherwise valid marriages are unworthy of federal recognition. This places same-sex couples in an unstable position of being in a second-tier marriage. The differentiation demeans the couple, whose moral and sexual choices the Constitution protects, . . . and whose relationship the State has sought to dignify.”

Moreover, Justice Kennedy added, DOMA also “humiliates tens of thousands of children now being raised by same-sex couples. The law in question makes it even more difficult for the children to understand the integrity and closeness of their own family and its concord with other families in their community and in their daily lives.”

Echoing his Romer decision, Justice Kennedy wrote, “The federal statute is invalid, for no legitimate purpose overcomes the purpose and effect to disparage and to injure those whom the State, by its marriage laws, sought to protect in personhood and dignity. By seeking to displace this protection and treating those persons as living in marriages less respected than others, the federal statute is in violation of the Fifth Amendment.”

[In this video, Windsor remarks on the DOMA ruling.]

Although the opinion was a narrow one from a bitterly divided Court, it had immediate beneficial consequences. Legally married same-sex couples became eligible to obtain a wide range of federal benefits and recognitions that had previously been withheld.

The Windsor decision, full of Justice Kennedy’s characteristic concern for individual dignity and solidly based in equal protection analysis, also provided the rationale to make the case for a fundamental right to marry in subsequent suits challenging state bans on same-sex marriage.

It influenced the legislatures of additional states to enact marriage equality laws, and was cited by state courts in New Jersey and New Mexico as they ruled in favor of marriage equality. It was also the basis of federal District and Appeals Court rulings in states as unlikely as Utah, Kentucky, and Oklahoma invalidating state DOMA amendments and statutes

Equal Dignity in the Eyes of the Law

Fittingly, the culmination of Justice Kennedy’s jurisprudence of dignity is embodied in Obergefell, the Supreme Court ruling issued on June 26, 2015 that declared marriage a fundamental right that must be extended to gay and lesbian couples.

The case, which is actually a consolidation of six marriage cases from Michigan, Ohio, Kentucky, and Tennessee, reached the Supreme Court when the United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit reversed District Court decisions in favor of the plaintiffs and upheld state bans on same-sex marriage. The consolidated case was named for Jim Obergefell, an Ohio widower who sought to have his late husband’s death certificate indicate his status as surviving spouse.

Obergefell’s story is told in a conversation with Katie Couric, which may be accessed here.

The excitement of young people as the Supreme Court heard argument in the Obergefell case on April 28, 2015 is apparent in this video.

On July 26, 2015, in an eloquent decision authored by Kennedy, and joined by Justices Ginsburg, Breyer, Sotomayor, and Kagan, the Court held that the Fourteenth Amendment mandates that states must both issue marriage licenses to same-sex couples and also must recognize valid marriages entered into by same-sex couples in other states.

Declaring that access to marriage is an element of “equal dignity” for gay and lesbian couples, Justice Kennedy said that the right to marry is a fundamental right inherent in the liberty of the person, and that “this liberty” may no longer be denied to same-sex couples.

Rejecting the arguments proffered by the defenders of the state bans on same-sex marriage that the purpose of marriage is procreation, Justice Kennedy nevertheless noted the special significance of marriage for couples–including same-sex couples–rearing children.

“Without the recognition, stability, and predictability marriage offers,” he wrote, “their children suffer the stigma of knowing their families are somehow lesser. They also suffer the significant material costs of being raised by unmarried parents, relegated through no fault of their own to a more difficult and uncertain family life. The marriage laws at issue here thus harm and humiliate the children of same-sex couples.”

He also refuted the opponents’ appeals to tradition, writing, “The limitation of marriage to opposite-sex couples may long have seemed natural and just, but its inconsistency with the central meaning of the fundamental right to marry is now manifest. With that knowledge must come the recognition that laws excluding same-sex couples from the marriage right impose stigma and injury of the kind prohibited by our basic charter.”

When the historic decision was announced on June 26, 2015, it was greeted with celebration and gratitude, as this video and this one both attest.

Justice Kennedy’s beautiful and profoundly moving conclusion has already become a staple reading at marriage ceremonies: “No union is more profound than marriage, for it embodies the highest ideals of love, fidelity, devotion, sacrifice, and family. In forming a marital union, two people become something greater than once they were. As some of the petitioners in these cases demonstrate, marriage embodies a love that may endure even past death. It would misunderstand these men and women to say they disrespect the idea of marriage. Their plea is that they do respect it, respect it so deeply that they seek to find its fulfillment for themselves. Their hope is not to be condemned to live in loneliness, excluded from one of civilization’s oldest institutions. They ask for equal dignity in the eyes of the law. The Constitution grants them that right.”

Justice Kennedy’s jurisprudence of dignity has significantly advanced equal protection of the law for lgbt citizens and thereby expanded liberty and justice. Moral disapproval of homosexuality is no longer a constitutionally permitted reason to deny equal rights to gay people.

Thanks to him, and to those colleagues of his who joined and may have helped refine his landmark decisions (Justices John Paul Stephens, Sandra Day O’Connor, David Souter, Steven Breyer, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Elena Kagan, and Sonia Sotomayor), the United States of America is today a freer country. Even as we are reeling from the massacre in Orlando, which has bared so painfully the hatred in which some people hold us, we can nevertheless be grateful for Justice Kennedy’s jurisprudence of liberty and dignity.

Enjoy this piece?

… then let us make a small request. The New Civil Rights Movement depends on readers like you to meet our ongoing expenses and continue producing quality progressive journalism. Three Silicon Valley giants consume 70 percent of all online advertising dollars, so we need your help to continue doing what we do.

NCRM is independent. You won’t find mainstream media bias here. From unflinching coverage of religious extremism, to spotlighting efforts to roll back our rights, NCRM continues to speak truth to power. America needs independent voices like NCRM to be sure no one is forgotten.

Every reader contribution, whatever the amount, makes a tremendous difference. Help ensure NCRM remains independent long into the future. Support progressive journalism with a one-time contribution to NCRM, or click here to become a subscriber. Thank you. Click here to donate by check.

|